FAYETTEVILLE — Defense has been the recent topic on the film studies, so here’s one final post to close out the 2013 defensive study.

The Hogs haven’t had a truly good defense since 2006, and even that one struggled against the pass at times. Chris Ash is in for a long rebuild, but what (or who) else can he look to in order to build a better defense at Arkansas? Does he need five-star recruits to play good defense?

Last Saturday provided some answers.

All great defenses can play man-to-man

Saturday was a disastrous day for those fancy spread offenses across college football. In fact, if I asked you to name the three most high-powered offenses in college football, you would probably respond with Oregon, Texas A&M, and Baylor. On Saturday, all three were completely shut down by defenses that had been struggling this year.

In the afternoon CBS game, LSU defensive coordinator John Chavis mixed press man-to-man with his signature Mustang zone coverage to baffle and humiliate Johnny Manziel into his worst game as a college quarterback. His previous worst game? Against the Tigers a year ago. Once is an anomaly, but twice is a trend. In the late afternoon in sunny Arizona, the Wildcats pounded the Oregon “we don’t want to go to the Rose Bowl” Ducks by a 42-16 score. Then in the ESPN primetime game, Oklahoma State dismantled Baylor 49-17 in Stillwater.

So what’s up with all three winners? They all won the same way. In a time where the media is in a frenzy over these fun and fancy spread offense, the football gods gave us Saturday so we won’t forget that defense wins championships: now, then, and forever.

Let’s start with LSU-Texas A&M. Chavis has Manziel’s number, and 2013 was even worse than 2012. Manziel was a horrific 16 of 41 for 224 yards with a touchdown and two interceptions. The Aggies handed the ball off just four times after their opening drive, so Manziel was everything for them, totaling 276 yards in 53 plays (5.2 yards per play) in the 34-10 rout.

Hello man defense. The Aggies are going for it on 4th-and-6 and have five receivers in the formation. LSU is using Dime personnel (4 DL, 1 LB, 6 DBs) and has man coverage on every single WR for the Aggies. The one linebacker is in a middle zone and is used as a “spy” if Manziel tries to scramble.

The safety is deep and is looking to help whoever comes in the deep middle. Notice how the outside cornerbacks are playing outside if the #1s. They are attempting to force the receivers to release inside so that they’ll have safety help if the receiver goes deep.

Texas A&M is very good at throwing deep sideline vertical routes, but by using press coverage, LSU’s defensive backs can be the aggressors and dictate how the plays will go.

Nick Saban switched to man coverage after his team fell behind 20-0 in the first quarter against Texas A&M in 2012, and the Tide held the Aggies to nine points in the final three quarters.

But when he attempted to bring it back in 2013, the Aggies were ready for it, using Mike Evans to torch the suspect Tide cornerbacks and jump up 14-0 before Saban scrapped in favor of his Quarters Rip/Liz modification (another topic for another day).

The Aggies eventually solved that one as well, but not before Alabama had built a 35-14 lead that would prove insurmountable.

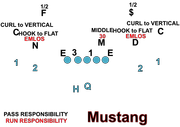

John Chavis was able to stay in man for almost the entire game because he mixed man coverage with his Mustang defense. Mustang is zone coverage from a Dime package. As the name implies, the goal is to get the fastest defenders on the field to stop a fast offense. LSU uses it often, in fact, it’s the reason that the Tigers are much less susceptible to spread offenses as, say, Alabama.

The best way to beat LSU is to play power football from a pro-style offense, as they are among the best in the nation at adjusting to a spread offense. Chavis has been on the opposite sideline of the worst games of the careers of Tim Tebow, Cam Newton, and now Johnny Manziel. So far in 2013, LSU is the only team to beat Auburn, and it did so in blowout fashion. Don’t be surprised if Auburn plays Alabama much closer than it played LSU.

Chavis’ ability to hound the spread with speed brings us to an excellent football maxim: the best defenses can play man-to-man. They aren’t exclusively man, but they all can play it. In a game where team really needed him, Mike Evans was held to 4 catches for 51 yards.

Who was covering him? Rashard Robinson, a true freshman. A south Florida prospect, the Hogs had gone after the 6-foot-2 lockdown corner, but he chose LSU and handled Evans in 1-on-1 coverage for most of the game. Impressive.

Quietly, Oklahoma State has spent the last four or five years recruiting speedy defensive backs, mostly from Texas. The Cowboys have led the Big XII in takeaways in three of the past four seasons. First-year defensive coordinator Glenn Spencer, who has been on staff since 2008, devised a simple yet brilliant scheme to stop the Baylor offense: make them beat man-to-man.

If the top of the diagram is confusing, Baylor likes to line receivers up outside the numbers, and ESPN’s cameramen did a poor job of zooming to catch the whole field. There’s a receiver and a press cornerback up there. Regardless, it’s man coverage across the board.

Oklahoma State knew that it had superior defensive backs that could run with the Baylor wideouts and it did just that. Where Oklahoma defensive coordinator Mark Stoops got cute and used lots of zone coverage (it worked for a while), the Bears eventually busted it down and won the game 41-12.

Baylor never broke through against the Cowboys, who lead 35-3 at the end of the third quarter. Almost half of the Bears’ 480 yards came in the fourth quarter with the game long out of reach.

So what is the lesson for Arkansas fans? The Hog defense needs one thing: speed, and lots of it. Speed enables a defense to play press coverage and be physical with wide receivers, and it allows a defense to play man coverage. If a defense cannot do those two things, it can’t ever be very good, especially in this modern era of high-powered offenses.

History lesson

College football comes and goes in cycles. The return to man defense to stop spread offenses is just a cycle. In 1991, in order to stop Houston’s Run-N-Shoot offense, Texas A&M defensive coordinator Bob Davie popularized the zone blitz, which helped ushered in an era of zone defense in college football. Things got even crazier in 1995, when Nick Saban arrived at Michigan State from Krypton from the NFL, carrying he and mentor Bill Belichick’s Quarters defense, an adjustment to the ever-popular Cover 2.

Meanwhile, Frank Beamer was causing trouble in the Big East with former cellar-dweller Virginia Tech. Beamer’s “Robber” defense powered the Hokies to the first of many conference titles in 1995. For the first time in a long time, defenses appeared to be ahead of offenses.

Jim Chaney was in the middle of the fun. Inevitably, offenses retaliated. Chaney was the offensive coordinator for Joe Tiller, a disciple of Dennis Erickson’s Oneback offense. Tiller used many of the same concepts and built an all-out spread offense at Purdue (1997-2008) which took the Big Ten by storm (recall my bye-week column on “quick-fix” spread offenses). Drew Brees led the Boilermakers to 9-win seasons in 1997 and 1998, but in 1999 they hit their first wall.

Purdue opened 1999 with a 4-0 start with Brees and were ranked 10th in the nation, the best ranking in school history. But a bout with Tom Brady and #4 Michigan in the Big House provided the formula for beating them. Michigan defensive coordinator Jim Hermann played a 4-2-5 nickel defense with man coverage on all Purdue receivers.

Brees saw his receivers covered by more athletic defensive backs and suddenly, the “schematic advantage” provided by the spread offense was negated. Purdue fell to 7-4 in 1999, including 1-4 against ranked teams. The one victory came against Nick Saban and 5th-ranked Michigan State by a 52-28 score. Someone forgot to tell Saban that simple man coverage with faster defenders was sufficient for stopping the Purdue offense, and Saban attempted elaborate zone schemes that blew up on him.

After starting 0-3 against Tiller, Saban finally had his revenge in 2000, using mostly man defense to defeat Purdue 30-10. By 2003, Chaney realized that the spread offense with less talent was eventually susceptible to faster defenses, so he jumped ship for the NFL to relearn the Oneback offensive concepts from a pro-style system. Tiller retired in 2008 without ever topping the success of his first two seasons.

As the spread offense grows in college football, so too will man defenses. It’s the cycle of football.

How does this apply to Arkansas?

If the Hogs want to stop the offenses they are facing the SEC, they need more speed in the defensive backfield. The LSU strategy of signing ulta-talented four-star recruits is probably out of Arkansas’ reach right now, but the Hogs need to continue to target high-profile defensive backs like Rashard Robinson that could contribute immediately.

Arkansas is better served using Oklahoma State’s strategy of stockpiling speedy defensive backs. Oklahoma State doesn’t recruit at a higher level than Arkansas, so there’s no reason Arkansas can’t do what they have done. From 2009-2012, the Cowboys’ average class ranking is 32.6 (per Rivals).

Over the same time period, Arkansas’ average finish is 30. Since 2009, Oklahoma State has signed 20 defensive backs (four per year). Only two of them were four-star recruits per Rivals, and those were balanced out by two two-star recruits, for a perfect average of 3.0 stars for those twenty. That class lacking obvious superstars is currently 3rd in the NCAA interceptions and will lead the Big XII in picks for the fourth time in the past five years.

The Cowboys are not intimidated by high-powered offenses are very difficult to beat without a strong running attack, and even then they use fast defenders to swarm the running lanes.

It seems obvious that the Hogs are already on this track. So far, the Razorbacks have five DB commits for 2014, and if the Hogs can land Raymond Wingo that would make six three-star recruits. Not all six are blazing fast, and those that aren’t will have to redshirt before they see the field.

The good news for the Arkansas commits is that everyone in the secondary not named Eric Bennett is back, so the Hogs have enough returning veterans to redshirt most of the newcomers. Wingo is the fastest of the bunch, and his blazing 4.31 40-time could equal immediate playing time. A secondary full of Wingos could fix the Hogs’ pass defense woes in a hurry.

Like Oklahoma State, Missouri has done the same thing as far as how its stockpiles talent. Like the Hogs, the Tigers are traditionally able to lure athletic 4-3 defensive ends into their system, so they have some studs to work with (DE Michael Sam is the SEC’s best defensive player right now). They have done an excellent job of following a solid recruiting pattern of adding size at defensive tackle and speed at linebacker and secondary.

The Tigers now have elite defensive ends leading a big, physical defensive line supported by a speedy back seven. Michigan State, another team that runs the Quarters defense that Chris Ash is trying to implement at Arkansas, has done the exact same thing. It should come as no surprise, then, that both Missouri and Michigan State are battling the Hogs in recruiting for players such as Wingo and Sharieff Rhaheed, a speedy outside linebacker from Florida.

If Arkansas is trying to emulate the success of those programs (and it appears it is), then expect recruiting battles with Oklahoma State, Missouri, Michigan State, Louisville, and others that have similar defensive goals.