FORT SMITH — It’s pure opinion, but if everyone started a list of the greatest Arkansans to play in the NBA almost all would leave off one of my top five: Jim “Country” King from Branch.

Branch?

Yes, Branch. I’m going to help you find it. It’s between Cecil and Caulksville in Franklin County.

And, if you are searching for a spot to put King on the all-time all-stars from Arkansas, he goes somewhere between Sidney Moncrief, Scottie Pippen, Joe Johnson and Corliss Williamson.

You say you don’t remember King? You are not sure if he’s a legend among Arkansas basketball legends?

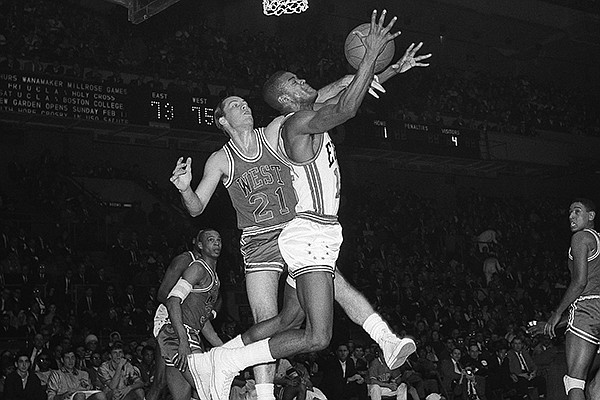

Oh, try asking the likes of NBA greats Jerry West, Jerry Sloan, Elgin Baylor, Nate Thurmond, Rick Barry, Oscar Robertson or John Havlicek.

You’ve heard of them. They know King. They played with him or against him, and all will tell you there’s never been a more fundamentally sound guard, tougher defender or better teammate.

I’m going to plead guilty to not knowing everything about King growing up. I knew he was an NBA all-star in 1968 and was involved in many playoff games. I recall watching him on TV as a junior high basketball want-to-be when King was a regular in the playoffs. Did I know he was from Arkansas? Vaguely.

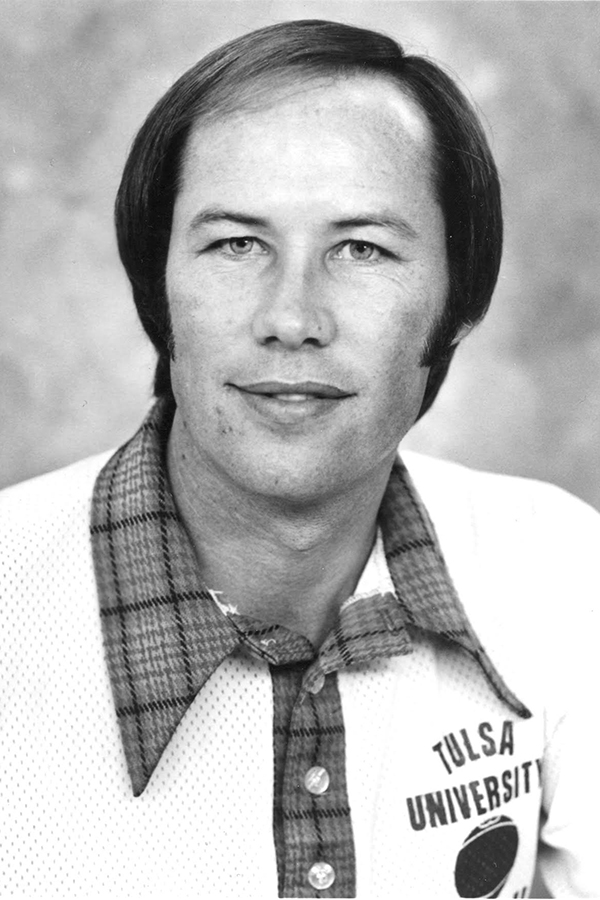

Our paths would begin to cross in 1978 when I was assigned the Tulsa beat as a cub reporter at the Tulsa World. King was the head basketball coach at Tulsa, one of the greatest people I’d ever met in sports. He was coaching the Golden Hurricane after a stint as head coach with Athletes in Action, a traveling team that preached the Gospel.

That followed a 10-year NBA career that included nine years with teams that made the playoffs. He played with the Los Angeles Lakers, San Francisco Warriors, Cincinnati Royals and Chicago Bulls.

Early in the first hours on the job in Tulsa was a day with Bill Connors, sports editor and my mentor for 14 years. He wanted to give me a scouting report on the area coaches and my new beats.

“You will love Jim King,” Connors said. “There isn’t a finer man, a better person anywhere. He’s a legend here in Tulsa. Oh, and he might offer to cut your hair. He’s a good barber, too.”

Just last week over lunch, Rogers banker Ron Wey, who played basketball at Southern Cal during King’s time with the Lakers, had the same kind of praise for King.

“There has never been a pro athlete with the class and character of Jim,” Wey said. “I idolized him during my time at USC. We’d go over to watch the Lakers practice. Wow. You want to see someone work in a practice?

“It was clear what kind of person he was then and he’s the same now. He made such an impact on everyone he ever touched.

“Jim traveled with AIA and delivered the Gospel everywhere he went. You keep track of points and rebounds as a sports writer. That’s not what is going to mean anything when you get to (Heaven’s) gates. It’s how you lived your life and the number of people you touched for Christ, that’s what is meaningful. Jim King was so good at that.”

HOG CALL WAS TOO LATE

Jim King played at Tulsa after Arkansas was late to recruit him out of Fort Smith High School, now Northside.

Jim King was good at everything. And he was great at basketball. It’s still a shame that Arkansas coach Glen Rose didn’t take him along with two other Fort Smith High School - now Fort Smith Northside - teammates in 1959. Rose finally did offer King a scholarship after he broke the scoring record with 21 points in the high school all-star game, and well after he’d committed to Tulsa.

King would become a two-time All-Missouri Valley player at Tulsa where it retired his jersey number. There were some games against Arkansas, too. Fans — mostly students — were livid when King came into Barnhill Arena to light up the Razorbacks. They hung Rose in effigy in the stands because he had not signed King.

“Coach Rose asked me to look at his neck after one of those games,” King said. “He told me, ‘That’s the rope burns you see – for not going after you.’ I know we beat them more than they beat us.”

All of this was recounted in an interview that lasted well over two hours a couple of weeks ago in Fort Smith. King, 77, has been spending time there of late.

King introduced his high school sweetheart, Marilyn, with an explanation that both had recently lost their beloved spouses. He currently lives in McKinney, Texas, to be close to grandchildren.

There was so much to cover and the time flew. Among the topics, how he was tagged with the “Country” nickname.

“We had moved from Branch to just outside of Fort Smith when I was in the sixth grade,” King said. “My brother and I would hunt on the way to school. Over the course of a few weeks we killed 52 possums while walking to school.

“So everyone called me ‘Country’ when I got to high school. I thought I’d lose that when I got to college, but there was a football player from Northside at TU before me. I walked in the dorm the first day and he yelled, ‘Country!’ So it never left me. I really didn’t mind.”

That’s because he deserved it.

“We milked cows before school and every night,” he said. “We ran traps for rabbits before school. I was proud of being called Country. Branch was and still is in the country.”

THE KAUNDART FOUNDATION

There was no doubt he wanted to go to Arkansas in the same class with high school teammate Tommy Boyer. Interestingly, he’s recently attended several Arkansas basketball games as Boyer’s guest.

“The problem was that I didn’t start until my senior year,” he said. “I was 6-2 as a senior, but I’d grown two inches during the year. And, I didn’t have to score much on that team. We had scorers. I handled the ball and played defense. I know (longtime Northside coach Gayle) Kaundart wanted Glen Rose to take me, too. Coach Rose said I was too slow and too short.”

The issue was that he never played guard in high school, always forward.

“But if you played for Coach Kaundart, you could handle the ball, with either hand,” he said. “I played for a lot of great coaches in the NBA, but Coach Kaundart was the best.”

The Grizzlies won 11 state titles under Kaundart, twice in King’s time.

“The only scholarship offer I had was Tulsa,” King said. “That’s not counting Rose offering after the all-state game.”

King wasn’t the MVP of the game, but only because the vote was taken at the start of the fourth quarter, per the usual in games like that. He scored most of his 21 points in the fourth quarter.

“I had never played guard until that game,” King said. “We were down with six minutes to go and I started shooting from outside. I made all four of my outside shots and we won.

“I’d never shot outside jumpers like that before. They all fell. Everyone booed when someone else got the MVP and he tried to give me the trophy.”

More importantly, Kaundart was waiting for him at the edge of the court.

“You still want to go to school on The Hill?” Kaundart said.

There were no letters of intent then, just your word. King said his word was good and he’d go to Tulsa.

King’s word is good, but he’s finally giving up some of Kaundart’s secrets. There was code for how the legendary coach changed his defenses. It didn’t come from sideline calls. It came from sequences written on the blackboard before games.

“No one could ever figure it out,” King said. “Most teams change defenses after made baskets or made free throws. It was more random than that with us.

“We’d come to the game and he’d have the sequences written. And, it would all be coded to our jersey numbers. He’d point to a player and the player would rub his jersey number.

“No player ever told about it either. We were that committed to Coach Kaundart.

“We played some zone, but mostly man. Our 20 defense was man, started 20 feet from the basket. The 30 defense was man half court. The 40 defense was man full-court.

“It was the same style of defense that Henry Iba taught at Oklahoma State. We went over the top of every screen.

“When Coach Kaundart would point to a jersey number, you better get it the first time or you were sitting next to him. We all got it the first time.”

Kaundart’s unspoken rules and penchant for drill work served King well in his tryout with the Lakers as the 13th overall pick in 1963.

“You never dropped to a knee or sat down after a drill,” King said. “You never showed you were tired. It was understood that you wouldn’t do that on the court if Coach Kaundart was there.

“And, we ran every drill right-handed, then left-handed — at full speed. It was drill after drill.”

Kaundart was a legend, but so was another Northside coach. Bill Stancil sent many a player to Arkansas to play football.

“I was scared of him,” King said. “I just played basketball, but you just feared and respected that man.

“I was waiting to see Coach Kaundart in the athletic department offices. Coach Stancil’s office was there, too. He came by me and stopped. I was sitting. I just stared at the floor hoping he wouldn’t notice me.”

With that King’s eyes filled with tears and his voice broke. Stancil wanted to know when King left for Tulsa.

“I didn’t even think he knew who I was, much less that I was going to Tulsa,” King said. “He said, ‘You know they are going to try to run you off? Tell them they can’t work you that hard.’ I’ve always remembered that. What we got from Coach Kaundart and Coach Stancil was unique. If you listened to those two men, you would be just fine.”

ON TO THE NBA

When King got to the tryout with the Lakers, the warm-up consisted of all the Kaundart drills.

“There were nine others trying to make the team,” King said. “Everyone was crashing into each other. They didn’t know the drills. Fred Schaus was the coach and he asked if I knew the drills. So I ran them and led the team through them.”

The tryout was in the Loyola gym with no air conditioner. It was unusually hot and the windows were open. Brutal smog filled the gym.

“We practiced for about two hours and when we finally stopped for a five-minute water break, everyone collapsed on the floor,” King said.

King did not. He jogged to the other end of the gym for some solo tip-in drills. If you went down in a Kaundart practice, King said, “it was because you needed an ambulance.”

King was hurting but didn’t show it.

“I didn’t know it, but West was sitting with Schaus and the owner, Bob Short,” King said. “They were only looking for one player, a guard to help West. West told them, ‘That’s the one I want.’

“It wasn’t over then because we played some exhibition games. But when I went in to sign my contract, Bob Short told me that’s when I made the team.”

Jim King was 44-82 in five seasons at Tulsa. He resigned in 1980, opening the door for Tulsa to hire Nolan Richardson.

The terms of the contract were a paltry $9,500, including his $500 signing bonus. The 13th overall pick in the 2017 year’s draft was over $5 million.

“I remember that teachers were getting $5,500 then,” King said. “It wasn’t much money and it might not have been the smartest thing for me to do.”

King could have remained an amateur and taken a job with Phillips 66. The Bartlesville, Okla., oil company hired the region’s best college players (mainly from Oklahoma State, Tulsa and Arkansas) to work in business and play on a traveling team.

“But if you took the signing bonus, that was it,” King said. “I couldn’t play for Phillips. You lost your amateur status. I just thought I had to try the NBA or I’d always wonder if I could have made it.”

The money did go up gradually, then spiked with the startup of the ABA in 1967. King’s top salary was $65,000 after an ABA team offered him a job as head coach and player.

“I was making $18,000 and Dallas (now the San Antonio Spurs) offered me $50,000,” Kind said, “but that sounded like too much pressure and I didn’t take it. That was sort of like the deal Rick Barry got. But the Warriors raised my salary then.”

STILL GETTING PAID

There has been some “found” money from his time in the NBA. The players association organized late in his 10-year career and so there is some money from that. But there was a nice surprise check three years ago.

“I got a call asking me to fill out paperwork,” King said. “They said it had to do with my likeness and there would be a check.”

Indeed, a check for $34,000 arrived. His grandsons helped explain it. King’s likeness is used in computer video games.

“They showed me how you can do it,” King said. “You can have different playoff teams play each other in video games. I was on nine playoff teams. And, when my teams are picked, I get paid. There have been several more checks, but not as big as that first one.”

Most of King’s signing bonus was gone before he got to Los Angeles. He bought an engagement ring for $125, then fixed his car that probably wouldn’t have made the journey down Route 66.

“I drove it all at night,” he said. “You didn’t want to try going through the desert in the day. My car didn’t have air conditioner.

“I remember spending the night in Gallup, N.M. I couldn’t sleep, so I went behind the motel to do some running. I almost passed out. I thought, ‘I’m out of shape and how am I going to survive the tryout.’ Then, the next morning on the way out of town I saw a sign that said elevation 5,200 feet. I’d gotten altitude sickness.”

The next day he pulled over in Needles, Calif., and grabbed an LA Times that had speculation on who what rookie would make the team.

“They were saying it would be Roger Strickland,” King said. “He had led the nation in scoring, 32 per game. But that wasn’t what they needed. I knew they wanted a ball handler and someone to play defense. They had West and Baylor.

“I prayed and had a peace about it. Really, I was prepared. If you played for Kaundart, you were always prepared. He taught us to be the first on the court, the last off.”

King was first to the gym, two hours before the tryout. It was empty and locked. That worried him, but it was the last of his problems with the Lakers.

“Most pro teams just did their tryouts going up and down the court in a scrimmage, but not Schaus,” King said. “He wanted to see our fundamentals, the drill work. So that was perfect for me.”

And, his defense was what was needed.

“They weren’t going to put West on the best guard,” King said. “Defense was what they were looking for. They wanted someone to cover Oscar or Havlicek so West would be fresh for those great fourth quarters. Some of those guys you weren’t going to stop, you just made it harder on them.”

King became close to West. He asked him to attend his summer camps outside Tulsa and West came.

“I still talk to him,” King said. “I can tell you that he’s the same as he’s always been. He’s the one who can pick out players like Steph Curry. His evaluations are always spot on. He sees attitude, coachability and if you give full effort.”

No one is going to argue that was King, and it didn’t take long for West to see it.