Is Mason Jones a late bloomer? Overweight as a senior in high school and not recruited by Division I schools, the Arkansas guard is now contemplating the possibility of an NBA career.

The co-SEC player of the year has a compelling story about the motivation to lose weight in order to become a great college basketball player. He was in the 270-pound range as a high schooler. After much hard work and discipline, Jones is a svelte 6-5, 200.

During a phone visit with hall of fame basketball legend Gail Goodrich this week, the Jones story was suddenly more relevant. The former Los Angeles Laker/UCLA great is a perfect illustration of a late bloomer and loved hearing about Jones.

Unlike the “too big” Jones, Goodrich was considered “too small” as a high schooler in Los Angeles. UCLA coach John Wooden discovered him as a junior while scouting another player in the city championships.

Goodrich would become the centerpiece as Wooden won the first two of his 10 national championships in 1964 and 1965. It was 55 years ago this week when Goodrich scored 42 points in a 91-80 victory over Michigan, a title game record for individual points at the time.

The 6-1, 170-pound lefty guard scored 40, 30, 28 and 42 in the four 1965 NCAA Tournament games. In 1973, UCLA’s Bill Walton scored 44 points on 21 of 22 shooting from the field to eclipse Goodrich’s record in a title game.

Walton was never small. He starred at UCLA and in the NBA as a 6-11 center. The Goodrich story is amazing because he was 5-1, 99 pounds as he enrolled in high school. Few could imagine he would become one of the game’s greatest. UCLA and the Lakers retired his number.

Reached at his retirement home in Sun Valley, Idaho, Goodrich was interested in the Jones story. He loves college basketball and followed the successful Arkansas run by former coach Nolan Richardson. That the Hogs pressed full court was of great interest. That’s how Wooden’s UCLA teams played.

“We spread the floor and pushed the tempo,” Goodrich said. “And we pressed. Those teams in 1964 and 1965 were not big, but we were quick. We relied on speed. Now we did have talent.

“That’s the way Arkansas played under Nolan. He had fast, talented teams. We wanted to get the tempo up and so did Nolan.

“Nolan’s teams were always faster than everyone else. I watched them.”

Sadly, there will be no one to watch this weekend when the Final Four was supposed to be played. The coronavirus wiped out the NCAA Tournament. Goodrich knows stories about past NCAA Tournament triumphs are all we can write these days.

“I got an email today from a friend with a New York Post story that this is the 45-year anniversary of Coach Wooden’s last NCAA championship team,” he said. “It’s what we are left to talk about now.”

Wooden’s last championship came 10 years after Goodrich’s 42-point title game.

“What happened that night is that I went to the line a lot,” he said. “I always wanted to go to the hoop. I never figured anyone could stop me.”

I explained that Jones plays the same way for the Razorbacks. He led the nation in free throws attempted this season (282).

“I liked contact,” Goodrich said. “If they knocked me down, I picked myself up and said, ‘Thank you, I’ll shoot my free throws.’ That was what happened that night.”

Indeed, Goodrich canned 18 of 20 free throws in his 42-point game. He made 12 of 22 from the field. Some were from long range, but there was no 3-point line in those days.

“I had a great night, no question,” Goodrich said. “But I just remember that the 42 points just happened. We were confident that we were going to win.

“I see some teams that seem to be happy to be in the Final Four. That wasn’t us. There was never a doubt we would win. I don’t think teams are like that the way we were at UCLA.”

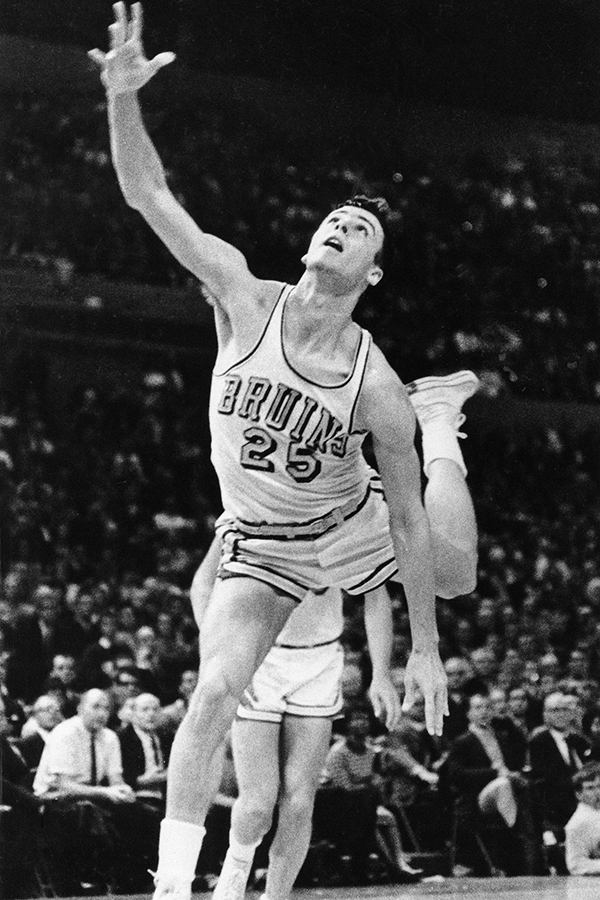

Gail Goodrich, UCLA's All-America guard, displays amazing form as he gets off a scoring shot against Michigan. Goodrich scored 42 points as he led his team to a 91-80 win over the top-ranked team in the nation in Portland, Ore., March 21, 1965. (AP Photo)

I recalled that, but only after some insight provided by a friend in Rogers, retired banker Ron Wey. We were talking about basketball legends two weeks ago when he suddenly volunteered Goodrich for an interview.

“He’s one of my extremely close friends,” Wey said. “You can call Gail and it will be a great interview.”

Boom, almost immediately I was on the phone with Goodrich, not once but twice as I thought of more questions. No problem, Goodrich said.

I knew Wey was close enough to Wooden to set up an in-person interview between Bo Mattingly and Wooden 12 years ago. Wey and Mattingly flew to Los Angeles to visit in Wooden’s apartment.

That Wey became close to the likes of Wooden and Goodrich is ironic. Wey played basketball at cross-town rival Southern Cal at the same time Goodrich was at UCLA. But he ended up living in the summer with UCLA star Keith Erickson and hung out as much with the Bruins as his USC teammates.

Goodrich loves Wey so much that he talked to a total stranger, a sportswriter in Arkansas, like he’d known him all his life. Each question produced a 15-minute answer.

The best part of the interview featured his growth spurts that took him from a tiny gym rat to a potential UCLA recruit. That Wooden picked him out of the trees is a testament to the vision of the legendary coach.

When asked about how Wooden recruited him, Goodrich talked for almost 30 minutes and concluded that he’d only scratched the surface.

The fun part is asking either Goodrich or Wey to talk about the other. They are close. Goodrich brought Wey to his induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass. Their friendship dates to Wey’s tight bond with Erickson, a Goodrich teammate.

“They lived together so Ron was always around,” Goodrich said. “We just became very good friends. Yes, he went to the other school, but everyone (at UCLA) liked him. We played a lot together in summers. If there was a pick-up game anywhere, we were in.”

And, it might be on the West Coast or in the Midwest. Wey took Goodrich to his home in southern Indiana during their college days.

“It was a summer trip and we played basketball with his friends in Terre Haute,” Goodrich said. “It was four days of driving. We were always in a 3-on-3 game. We drove cross country.”

Wey laughs about trying to take Goodrich on his first hunting trip in Indiana. A training stop went bad just before the actual hunt.

“I was setting up a can on a fence post to show him how to shoot a 12 gauge shotgun,” Wey said. “Next thing I know the gun went off. Gail had fired a shot and the gun was not on his shoulder. It kicked him in the face and there was blood everywhere. That ended the hunting trip.”

Goodrich didn’t laugh when telling his version. He said, “I’m from L.A. I never hunted and I still don’t fish much.”

It was basketball from an early age. Goodrich’s father was team captain for the USC basketball team, something that makes his stardom at UCLA highly ironic. Wooden was early to the party in the Goodrich recruitment, USC only a mild factor at the end.

The Trojans ignored Goodrich because he was always deemed too small. He starred at UCLA as a 6-1 shooting guard. That was after growing one foot from when he enrolled in high school.

“I was 5-1, 99 pounds when I went to the 10th grade,” Goodrich said. “But I had some skills.”

Indeed, Goodrich had talent and amazing quickness. He was impossible to guard. The lefty had Globetrotter-like skills and he was a fierce competitor never shying away from contact at the rim whether that was in the tough L.A. city leagues, the Final Four or as he helped the Lakers to championships with Jerry West, Elgin Baylor and Wilt Chamberlain. Goodrich was a five-time NBA all-star.

“I grew up with a basketball in my hands,” he said. “My dad started me playing when I was five or six. He was a college ref and he took me along.

“But I was so small that a lot of times I played with a volleyball. My hands were too small for a basketball.”

That lack of size did provide motivation.

“It made me tougher mentally,” he said. “I was always confident, probably bordering on cockiness.

“I do remember mentioning to my parents that I wished I was bigger. My mom would say, ‘You will grow and God gave you ability.’ I was given certain skills and I played with great passion.

“And, I played basketball all the time, probably to a fault.”

At some point, his father began to buy him basketballs and not just any basketballs.

“I had a leather ball that summer when I was in the ninth grade,” Goodrich said. “No one else did. I walked to the gym where the high school team played pick-up.”

It was organized with the Poly High coach in the stands.

“Our school at that time had highly structured ways of picking teams,” he said. “It was based on height and weight, along with ability. We had a varsity team, junior varsity, then A, B, C and D teams.

“These summer games would include all those levels, but the older players picked the sides for the game. I had skills, but normally I would have been too small to be picked.”

Except he had an ace to play, that leather basketball. All of the other balls in the gym were rubber.

“I brought my ball and the older boys knew if they didn’t pick me, I’d go to the other end with my leather ball,” Goodrich said. “So I got chosen every time.

“The varsity coach was watching and I guess he saw something in me. When he set the teams in the fall, I had hoped I might make the B team as a sophomore, but he picked me for JV.”

Goodrich earned the starting point guard spot as a 5-4, 99-pounder. Every other team member was over 6-0. He made all city JV as a sophomore. He moved up to varsity as a 5-8, 120-pound junior.

“I scored 20-something in the first round of the city tournament,” he said. “There were a lot of players better than me, but I was getting better.”

It was in that game that he got a break. Wooden attended and spotted Goodrich.

“He sat about four rows up in the stands with Jerry Norman, his assistant coach,” Goodrich said. “They were there to watch someone else, but he told his assistant, ‘I like the little left hander. He’s a smart player. If he grows, someday he might help us.’”

His parents were sitting a row in front of the UCLA coaches.

“My mom was so proud,” Goodrich said. “She turned around and asked, ‘Do you mean that?’ Coach Wooden said yes. That was our first introduction to UCLA.”

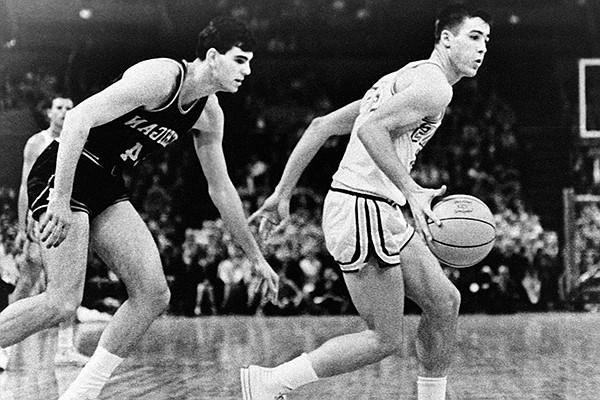

The next round included a game against a potent full-court press and a one-on-one matchup between Joe Caldwell and Goodrich.

“Caldwell was city player of the year,” Goodrich said. “He was 6-5 and would be a great pro. We lost, but I was not going to let him take the ball away from me. We began to get letters from UCLA and we learned they’d asked for my transcript to see if I would qualify.”

There were instructions to improve in a couple of courses, but qualifying would not be an issue.

“I got another growth spurt the summer before my senior year,” Goodrich said. “I was 5-11, 135. UCLA came to see me play on a good summer team. They said they were going to take a closer look.

“But at that point, that was it. USC had no interest. There was a new school in Santa Barbara with interest, but they didn’t have scholarships. I wasn’t going there.”

“My father really loved what he saw with Coach Wooden,” Goodrich said. “We went to see a UCLA practice. The fundamentals taught were incredible. My father said, ‘If he offers you a four-year scholarship, that might be worth consideration.’ USC had not even offered anything.”

It all fell in place in late February when Goodrich scored 29 points to win MVP in the city title game.

“Our team won, 52-39, and I played with a chipped bone in my ankle in the second half,” he said. “It was a good game for me and Coach Wooden came to see me after the game.”

It was a simple discussion.

“He just said they would like to offer me a scholarship,” Goodrich said. “We had mid-term graduation. It was a Wednesday night. I told him graduation ceremonies were Friday night. He said, ‘We can enroll you Monday morning.’ That was all there was to it. Monday morning I was a UCLA Bruin.”

USC began to show interest, perhaps believing they could grab Goodrich based on his father’s ties to the Trojans as a supporter and former captain, but there were no offers.

USC really wasn’t considered anyway.

“They didn’t have a way to get me into school until the fall,” Goodrich said. “My mom didn’t want me to be out of school all that time. Anyway, I figured Coach Wooden was the only one who had really been interested all along. You should go where you are really wanted.”

Goodrich didn’t begin basketball practice until the next term.

“I played freshman baseball that spring,” he said. “We didn’t want my (eligibility) to start until the fall semester. I watched basketball practice.”

It probably was soon afterward that Wey entered the picture, even as a USC player. It’s been a tight relationship ever since.

“You go through life and certain people you make a bond with,” Goodrich said. “You have lots of acquaintances, but very few really close friends. Ron and I are close.”

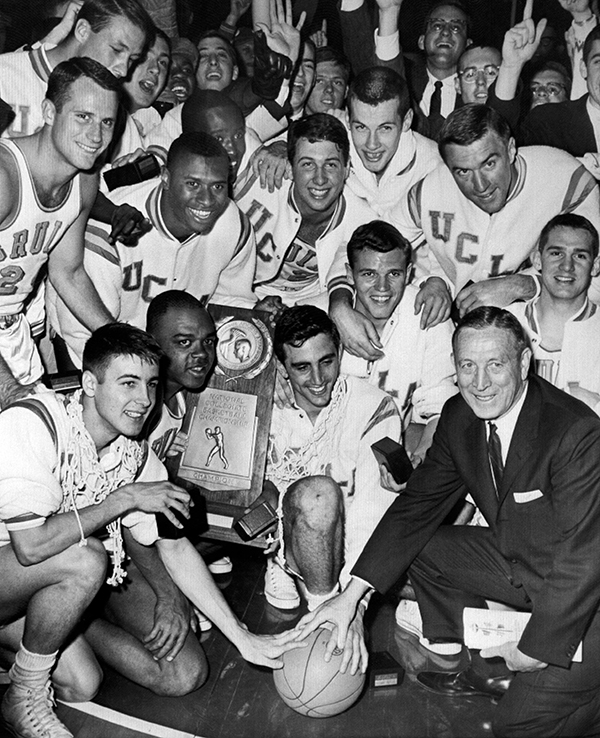

UCLA coach John Wooden, right, and members of the Bruin team smile following their 30th consecutive victory - 98-83 over Duke - that brought them the NCAA basketball championship trophy, March 22, 1964, in Kansas City, Mo. Players in front row are, from left: Gail Goodrich, Walt Hazzard and Jack Hirsch, holding trophy. Man directly behind Hirsch and Coach Wooden is Keith Erickson. The rest of the team is unidentified. (AP Photo)

Obviously, Goodrich was close to Wooden, too.

“I was blessed in that way with Coach Wooden,” Goodrich said. “He took an interest in my children. My two daughters grew up in L.A. and became close and often visited him at his apartment.”

Goodrich recalls simple pregame talks. Wooden’s preparation in practices were so good, that he didn’t say much when it was game time.

“He was never big on talks in pregame,” Goodrich said. “One of the things he said a lot, ‘Do your best and look in the mirror. Your best is good enough.’ He never talked about winning.

“We were the underdog in ’64 against Duke. But in the pregame talk, he just said, ‘You got here playing a certain way and that’s all you need. Press and rebound.’ Then, he asked us if anyone remembered who finished second in ’63. I knew, but I didn’t raise my hand. His point was no one remembers the second-place team. He said, ‘Now go out and play.’

“We got to the championship game in ’65 and he had a short speech again. He just said, ‘Play the way you are capable and you will be happy with the results.’ I know he watched film of the other teams, but we didn’t. He always said, ‘Be concerned with how you are going to play, only what you control.’

“That’s just the way Coach Wooden coached. The preparation in practice was so good that we didn’t worry about what the other teams did.”

Told that Richardson had similar philosophies, Goodrich said, “I believe that. We were very talented and so were his teams.”

Told that Richardson admired the Wooden full-court press, especially when Lew Alcindor played at the front of the press, Goodrich confirmed the same assets Richardson saw.

“With your center there, he affected the vision of everyone,” Goodrich said. “That was a huge advantage.”

Obviously, some of Wooden’s best teams featured great centers like Walton and Alcindor.

“But he never sacrificed quickness for size,” Goodrich said. “Coach Wooden always told me that quickness was the most important aspect in any sport.

“We had a discussion on that one time and I said, ‘What about golf?’ He thought a minute and said, ‘It’s in golf, too. The quickness of the club head at impact is the most important part of golf.’ There was no dispute.”

I’ve learned not to dispute anything from Ron Wey. If he says he can set up an interview with a hall of famer, get ready for something special.