I have ties to a lot of areas, including the golf community in Oklahoma. I was the golf writer at the Tulsa World for more than one decade. I got close to a lot of folks.

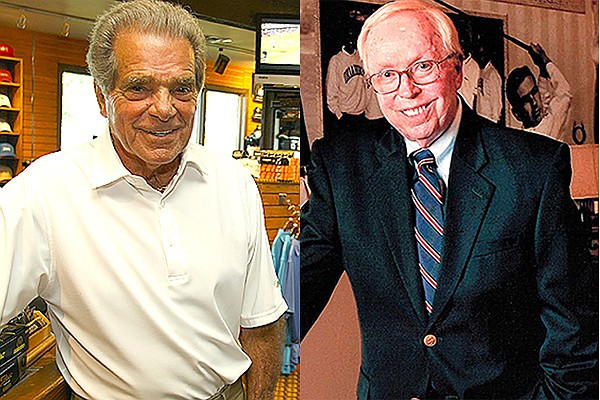

Two of my favorites were pros Buddy Phillips at Cedar Ridge Country Club and Jerry Cozby at Bartlesville’s Hillcrest Country Club.

Phillips died Friday at 85. Cozby passed on Sunday at 79.

I’m deeply saddened. I knew them intimately during my days as golf writer. I covered their sons (Tracy Phillips, Cary Cozby, Chance Cozby and Craig Cozby) in junior and college golf. I played at their courses, always as their personal guest.

But my sadness goes beyond those two men. Bee Lindsey, the older brother of Razorback great Jim Lindsey, passed away this week from complications due to covid-19.

In learning of Bee’s loss, I also was told of another Forrest City legend's battle against covid-19. Jim Williams, one of the star players on the 1964 Arkansas national title team, has been battling covid-19 for most of the summer. He’s not out of danger yet.

Williams, long a successful real estate man in the Dallas area, is one of my favorite Razorbacks. He is one of the kindest gentlemen I’ve known. He often sends me wonderful notes about something I’ve written. They are thoughtful and on point.

I’ll have a long prayer list over the next few days.

I have some good stories on all of these men. I’ll tell a few about the legendary Oklahoma golf pros here.

I met Cozby in 1985. Out of the blue, I got a call that began, “I’m one of your readers. I love your golf column every Sunday. It’s a must read for Oklahoma golfers. Would you write something for me?”

That doesn’t sound like something you’d hear from a man like Cozby. He was so humble.

Quickly, he explained that he’d been named national PGA club pro of the year. The organization’s magazine needed a profile and he got to pick the writer. It paid $1 per word. Would I do it? Oh, one other thing, the story needs to be over 2,000 words.

Wow, I’d be glad to drive to Bartlesville to spend some time to gather material to do that kind of piece justice. And, by the way, “Jerry, you just answered a prayer," I told him. "My wife and I are trying to scrape together enough money for a down payment on our first home. A $2,000 check will do it.”

The trip to Hillcrest was glorious. First, you have to know something about Bartlesville. It was long the home of Phillips 66, a great Oklahoma oil company. Hillcrest is a great club, with a course built by the legendary Perry Maxwell.

If you know golf course architecture, you know that Maxwell built Southern Hills, Prairie Dunes and many other less known Oklahoma courses — some only nine holes — that are spectacular.

Cozby drove me in a cart for the entire course, proud to show off a beautiful piece of Oklahoma land used to its fullest by Maxwell. It was interesting that we drove the layout backward. I didn't understand at first.

"A Maxwell course has to be played backward," he said. "Your tee shot is set up by the pin setting and the green. You must be on the correct side of the fairway. You will notice that with all the Maxwell courses."

I had not thought about that before, but eventually realized that's exactly how you play the great places like Southern Hills and Prairie Dunes. It was especially true at Dornick Hills, in Ardmore, where Maxwell was buried.

I found Maxwell's grave on a hilltop tee at Dornick Hills while covering the Oklahoma Amateur. Interestingly, one of the Cozby boys was playing, just ahead of a good run with the Oklahoma Sooners.

While covering junior golf and college golf, I eventually learned to walk a few holes with Cozby when his sons were playing. You'd learn the course and the nuances of the game. And, he did it in an easy, subtle manner that could be appreciated, always the gentleman.

Cozby was a pro at Hillcrest for 41 years. His service to his members was legendary. I interviewed a handful of members the day I went to Bartlesville to compile that story for the PGA magazine. Over and over they told me that “Coz” made members feel like each was the most important person to step out of their car at the club.

Member tournaments at Hillcrest were operated like the Masters. Everything was done perfectly. Preparation and execution of each event was always flawless.

You heard the same things about Phillips, the pro at Cedar Ridge for 40 years. Phillips and Cozby were the same in that aspect of their jobs, incredibly good at the details. There was never one thing out of place or missing. But they were also vastly different.

Phillips was a flashy dresser. Cozby rolled in a much more conservative manner. But they trained great staffs and featured great merchandise in their shops. Both raised unbelievable boys, now men all doing well in the golf business.

There was a similar tour of Cedar Ridge in a golf cart with Phillips, just a month ahead of the 1983 Women's U.S. Open. He opened my eyes to another way to play golf: avoid the worst of the trouble spots.

This time, we played in our minds starting on the first tee, with Phillips noting the trouble spots to either side of the landing areas. While he said there were few "bail out areas" at Cedar Ridge, there were some places that were better than others.

"When you play an Open course — and this is every bit of one — the key is where you leave yourself with misses both off the tee and around the green," he said. "You can eliminate a bad score here with that in mind, and you can play the other great courses in Oklahoma the same way."

You learned the secrets to golf around Phillips or Cozby, or the way to run a golf shop or how to work with membership. You don't last four decades at the same club unless you are giants. I learned to seek their advice and wisdom. None were better.

I spent more time at Cedar Ridge than about any place in Tulsa because of my relationship with Ed Beshara, a founding member there. Ed took me to lunch at Cedar Ridge about once a week over a 12-year period. Many times, Phillips joined us. He reveled in out dressing Ed, the owner of the finest clothing shop in Tulsa. They both wore silk pants and colorful jackets.

Ed was an avid golfer, just not a good one by the time I met him in 1978. But Phillips made sure he had the equipment that fit him best without wasting money. I appreciated that about Phillips. He probably could have sold a new set of clubs to Ed every year, but didn't.

It was soon after I met Ed that he invited me to play in his celebrity charity event at Cedar Ridge. Soon after I became his partner in the Ridge Run, a wonderful member guest event at Cedar Ridge that was one of the top events in Oklahoma. The tournament was a must for the state’s best players.

You might make a decision in business to land a spot as a guest in the Ridge Run. It was a big deal in my Tulsa days.

I got my spot with Ed because his regular partner, basketball coach Nolan Richardson, signed a deal with a new shoe company. There was a big AAU tournament the same week as the Ridge Run sponsored by the shoe company.

I was playing almost no golf in those days, but when Ed asked me to play I spent three weeks (one of them while on stay-at-home vacation) to work on my game. I had no home course and didn’t play enough to have a USGA handicap.

That first year Phillips sat down at lunch with Ed and I and we discussed my handicap. I’d been playing some public courses (LaFortune, Page Belcher and Mohawk) in Tulsa for most of my golf. I was shooting 78-85. Cedar Ridge is about six or seven shots tougher than any of those.

Phillips concluded that I couldn’t break 80 at Cedar Ridge, one of the toughest courses in Oklahoma if not the nation. Jan Stephenson won the 1983 U.S. Open at Cedar Ridge with a 6-over total, and that was after Phillips wisely widened the fairways and softened the rough.

That is why Ed was lobbying hard for extra strokes for me and told Phillips, “Hoss, he can’t break 85 here.”

Phillips put me in as a 12 handicap and said he wouldn't have to apologize to anyone. He said, "I doubt you are dangerous at a 12 on our course."

The handicap was a little high that first year. I probably played to an 8 in the tournament, but shooting 78-79 didn’t raise any eyebrows.

The next year things changed because I began working on my game several months ahead of the Ridge Run. I found a good teacher in the area, Marshall Smith from Miami, with solid results following in a hurry.

Just weeks before the Cedar Ridge gala, there was a good qualifying score with partner Ron French in the Tulsa Golf Association city 4-ball. We made the 16-team championship flight when I made five birdies at Mohawk.

So when the Ridge Run rolled around, we sat down at lunch again at Cedar Ridge. What should we do with my handicap?

The handicap is a big deal in the Ridge Run because the format is modified Stableford. It’s a point system based on values assigned to eagle, birdie, par, bogey and double bogey. You are given a goal based on your handicap.

We all knew that I was playing much better. Phillips thought an 8 handicap was fair. Turns out, it was way off that summer.

Things got interesting when Ed broke some ribs in a fall while battling a massive tarpon two weeks before the tournament. He subbed his son-in-law, Kent Dunbar, as my partner, a much better player than Ed.

Turns out we both played well, much better than our handicaps. Phillips knew things were going to get interesting the day before the tournament when he put me into the Horse Race, a fun betting event with nine teams. I played well in a pressure-packed setting.

A golf horse race is a massive event with all nine two-man teams going off No. 1 tee together. One team is eliminated each hole until a winner is crowned on the ninth green.

The crowd — all in golf carts — is massive. Everyone is there to attend the pre-tournament party that night. I’ve never felt such nerves. The field is matched based on handicaps. I was the worst-rated player in the field with an 8. I was paired with a former pro with a plus 2.

It’s alternate shot, the most pressurized format in golf. We made it five holes before being eliminated. Someone chipped in to oust us in a chip off. I did nothing wrong. I was pleased, except Phillips wasn’t. He watched me with the critical eye of a pro and saw no flaws.

“Clay, I think we messed up on your handicap,” Phillips said. “I’m going to let you play as an 8. You are better than that, but I’ll take the heat if you get it going the next two days.”

I did. I shot 71-72 and made a ton of birdies. If you make birdies in Stableford, you pile up massive points.

The highlight came on Sunday on the 17th fairway when Ed and Phillips came rolling up in a golf cart. They were checking scores in our flight. Dunbar and I figured we were in contention to finish in the top five and earn a prize.

But there was a lot more riding on our round that maybe a new driver or golf bag, the bottom level prizes in our flight. I’d forgotten about the Calcutta betting. It was out of hand in those days and the pay out was about six months wages for a sportswriter.

I had no skin in the game, but Ed had bought our team. He stood to make five figures if we won.

“Don’t throw a shoe now, because old Hoss here stands to make a bunch of money,” Phillips said.

Then, he added, “I think ya’ll are up a few points. I think you can coast home with bogeys. Let’s see how you handle the heat.”

We did better than that. We made three pars out of our four chances on the last two holes and won by a considerable amount. I handled the heat, but turned it up on Phillips. Members were grumbling.

I got a plaque that I still treasure. Ed handed me a wad of $100s out of his take from the first prize in the Calcutta. It was almost as much as the check for writing the Cozby story.

Phillips presented me the plaque with one short comment, “Next year you will have to be a 2 handicap. I probably won’t hear the end of this for a few weeks. Ed has already told everyone in the club that I set your handicap. I’ll take the heat because all you did was play your ass off for two days. You didn’t claim to be an 8.”

Then, the next week, I played in the member guest at Tulsa Country Club. Dave Bryan, the TCC club pro then, must have talked to Phillips because he put me in as a 2 and I backed it with 73-72 and our team finished near the top.

That ended my golf for a bit. I moved to Northwest Arkansas to begin Hawgs Illustrated magazine. Golf took a back seat and the clubs gathered dust in the garage.

Fast forward 10 years and my golf time increased, but my practice work ethic did not. I established a handicap for the first time at Lost Springs in Rogers. I was a solid 9 and felt it was about right. My brother, Butch, invited me to Aiken, S.C., to play in his member-guest tournament.

So when I arrived at Aiken, we went to the club for a practice round. I handed the club pro my handicap card. I finally had what I thought was a legit handicap.

We finished our practice and I looked at the scoreboard flights. We were put into a much lower group than I anticipated. The club pro grabbed us for a conference in his office.

“We entered your ID number and this popped up,” he said, then pointed to a 2T by my name.

I’d never seen anything like it.

“You played in some tournaments 10 years ago and shot consistent scores below your handicap,” he said. “The club pro entered them to start a handicap for you. You are a tournament 2. Do you remember the pro at Cedar Ridge?”

And, there was less of an argument the next day when we won low-day money when I made a hole-in-one and three birdies to make my target total despite my two handicap. I don’t remember what an ace scores in Stableford, but it’s a bunch.

But back to that question in Aiken, S.C., 15 years ago, do I remember Buddy Phillips?

Yep, always in a fond way. He’s a man who could take the heat.