FAYETTEVILLE — The legendary George “Iceman” Gervin had a thigh contusion and had to miss a few games early in the 1981-82 season for the San Antonio Spurs.

Enter Ron Brewer, whom the Spurs had traded for midway through the previous season.

With Gervin, a legendary scorer who averaged more than 30 points per game twice in his NBA career, sidelined, Brewer went off. The 6-4 guard from Fort Smith and the University of Arkansas scored 39, 40 and 44 points, ascending career highs, to help the Spurs beat the Cleveland Cavaliers, the New York Knicks and the Los Angeles Lakers midway through a sizzling 9-1 start.

“It was a perfect situation,” Brewer said. “The offense was built around Iceman. They set single picks, double picks, staggered screens. The offense was get him open and let him do his thing.

“So I’d never been in a situation where I had the green light to shoot the ball at will. I came in for him for three games, and those three games became my career highs.”

Brewer was named NBA Player of the Week after shooting 50 of 75 (66.7%) from the field, 23 of 25 (92%) from the free-throw line and averaging 41 points in Gervin’s absence.

Best Pro Hogs

Who are the best former Arkansas Razorbacks to play professional basketball?

In the upcoming days, we will present a list, in descending order, of the 10 best Razorbacks to play in the professional ranks. This list was compiled after consultation with media members, coaches and assistant coaches who are familiar with Arkansas’ all-time roster.

https://www.wholeho…">No. 10: Oliver Miller

https://www.wholeho…">No. 9: Joe Kleine

https://www.wholeho…">No. 8: Patrick Beverley

“They were saying, ‘Dead-Eye Brewer, best shooter in the West.’ That’s what people were saying in San Antonio,” Brewer said.

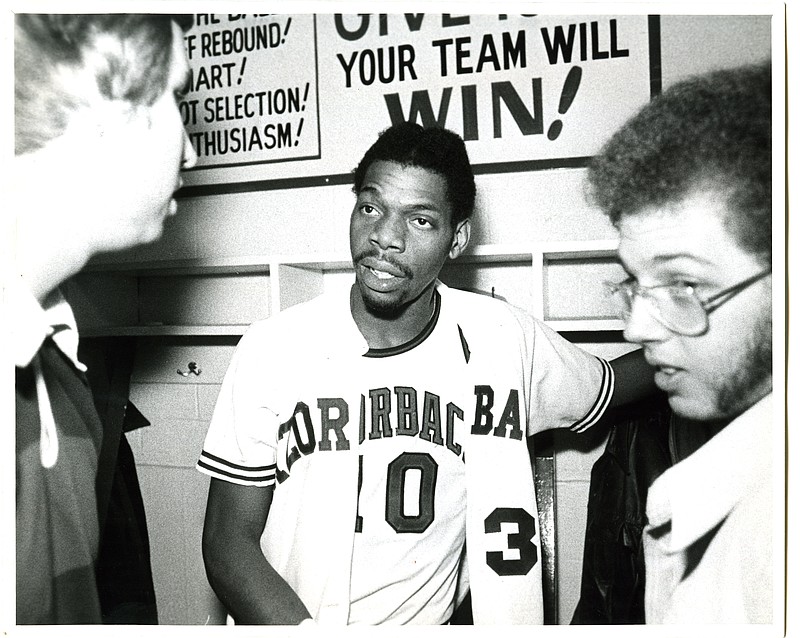

Sure, it was a small sample size, but also a glimpse into the scoring prowess of Brewer, one of “The Triplets” who ignited the passion of Razorback fans in the late 1970s and became the No. 7 pick in the 1978 NBA Draft by the Portland Trail Blazers.

Brewer, who averaged 11.9 points in 501 games during his eight-year NBA career, is the No. 7 player on the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette’s list of the top Razorbacks in the NBA.

Brewer inherited the nickname “Boothead” from his older brother and transferred from Westark Community College in Fort Smith to play his final three seasons with the Razorbacks.

The height Brewer got on his jump shot was a calling card, and his shooting touch — which led to career 56.6% shooting with the Razorbacks and 45.9% shooting in the NBA — was undeniable.

“Boothead could score,” said Darrell Walker, who was three years behind Brewer at Arkansas before joining him in the NBA. “He had some great seasons.

“He was a good shooter and he elevated his shot. That made it easier for him to get his shot off. And he moved well without the ball. Boothead was an unbelievable athlete, too. I wish he could have played a few more years, but he was a heck of a player.”

Brewer is inextricably linked to Arkansas basketball for being a Triplet with Sidney Moncrief and Marvin Delph, and as the father of Ronnie Brewer, a Razorback from 2003-06, who also enjoyed an eight-year career in the NBA with the Utah Jazz and five other clubs.

Ronnie Brewer has read up on and seen clips of his dad’s glory years with the Razorbacks.

“I think during that time, Razorback athletics was really at an all-time high,” he said. “The football team was really, really good. The basketball team was really, really good. I think it was the start of something very special, with Eddie Sutton changing the face of Arkansas basketball and making it a national household name.

“To be able to see some of the throwback games and how highly regarded my dad was, and Sidney Moncrief and Marvin Delph, you know, it allows me to get a greater appreciation for how great they were and all the things they achieved at Arkansas. To make it as far as they did and to turn the program around like that, it really means a lot to I know him, myself and a lot of Razorback fans that were able to experience it.”

The elder Brewer calls Razorback fans the best in the world.

“That’s one of the reasons my wife and I did everything in our power to make sure Ronnie became a Razorback,” he said. “What I wanted him to be able to experience was playing for your state team, playing well and seeing the excitement and the feel that I had about the best fans in the world watching you play.

“I know when I played … we didn’t care who got the limelight or who got the bulk of the interviews or the laurels, we just wanted to win. And because of that, it made us become a great, great team a great unit and to this day it almost seems like it solidified it so tight because it’s been a long, long time since we played on the Razorback court, but the relationship we have that we built from that has been everlasting and it’s been unbelievable.

“We also brought a lot of people together during times that either good or bad, they would put all that aside to come and watch Razorback basketball.”

The Brewers rank 15th and 16th in scoring in Arkansas history: Ron is 15th with 1,440 points and a 15.8 scoring average in three seasons; Ronnie is just behind with 1,416 points and a 15.7 scoring average.

Ronnie said his father could take him in a one-on-one game, up to a point.

“When I was younger, my dad was for sure winning all those battles,” he said. “I think once I got older and hit a growth spurt and I got a little bit bigger than him, it kind of flipped the script. I was kind of a little stronger, more athletic, so I started winning a majority of those games.”

The younger Brewer grew to 6-7 around the 10th or 11th grade.

“The good thing was I know I couldn’t handle him,” Ron Brewer said. “He was 3 or 4 inches taller. He was 6-7 or 6-8 and when he was really playing his good basketball, he was 235-240 pounds. The biggest I ever got was 190. That, over a period of time, that would wear me down.”

Ronnie Brewer, who went to all kinds of games with his dad as a youngster, was elated that Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport had a nonstop flight to Salt Lake City when he played for the Jazz. Ron and Carolyn Brewer were regulars at Jazz home games during those years.

“They were able to get nice flights year-around, and whenever they felt it was a good time and we had a good stretch of home games they would come out and watch as many games as possible,” the younger Brewer said. “I loved having my family at the games, seeing a familiar face. It was always great when they could come watch all the games.”

The elder Brewer hit many big shots as a Razorback, but maybe none more memorable than his buzzer beater from the top of the key to sink Notre Dame in the third-place game at the 1978 NCAA Final Four in St. Louis.

The Razorbacks had called timeout with the score tied 69-69 and 10 seconds remaining.

“When we called timeout, you could imagine Coach Sutton over there drawing up a play for what he wants to happen in 10 seconds,” Brewer said. “But I’m looking at it, the game is tied, and this is my play. It wasn’t that he was worried about it. He knew that if I missed it we were going to overtime. But he realized if there was anybody he wanted to take a last-second shot, it was me.”

With the ball in his hands, Brewer took his time crossing half court before eventually making his move.

“I was supposed to penetrate, find Sidney cutting to the bucket or find Marvin on the perimeter for a jumper,” Brewer said. “I heard it, but I didn’t hear it. So when I came down the floor, I came down nonchalant. I had to get in my area first. When I got in my area, I gave him three-quarters of my body, went one way and came back the other way. When I went up for the shot, I knew if he wasn’t there, it was a bucket. I’m fortunate it went in.”

The long-distance shot at the horn gave Arkansas a 71-69 victory, its best finish at the NCAA Tournament until the 1994 NCAA championship season.

When Brewer left Fayetteville in 1978, he had no intention of returning to Northwest Arkansas.

“It’s just there wasn’t a lot of things happening for a Black student or a Black kid,” Brewer said. “We didn’t have any problems. We had preferential treatment when we were in school because we were athletes. But I saw some of the things going on with my peers.”

Brewer and his wife, the former Carolyn Torrence of Ogden, had a home in Portland when his playing career ended. But after a few years, he decided to finish his degree and look for jobs in coaching, so Carolyn, also a former Razorback basketball player, persuaded him to return to school.

“When I left in 1978, I wasn’t planning on coming back at all,” Brewer said. “But I came back and got my degree. I came back in 1990. We’re talking about 12 years. In a 12-year period of time, Fayetteville changed completely.

“It’s a place right now where Ronnie’s here living. I share with a lot of people I went to school with about this is the best place in America to live. I’ve got a lot of people moving up this way. It’s a place that I’m very happy to say is my home town.”

The Brewers have five children: sons Stephen, Kenny and Ronnie; and daughters Candice Brewer Graham and Elisha Brewer. Candice played basketball at Tulsa, and Elisha ran track and field with the Razorbacks.

Ronnie, who is now assisting former mentor Brad Stamps with the Fayetteville High School basketball team, had plenty of options to call home when he wrapped up his NBA career with the Chicago Bulls in 2014. He also chose Fayetteville.

“We ended up going through the public school system here and going to the Boys & Girls Club, making friends and meeting lifelong mentors,” Ronnie Brewer said. “Our love for Razorback athletics, not just basketball but all athletics, men and women, it’s a nice place to raise a family, a nice place to live and it’s somewhere we call home.

“I could have lived anywhere in the United States, and my dad could have lived anywhere in the United States, but we felt like this is home. That’s why we came back and that’s why we reside here because it’s home to us.”