Competitive fire shows up in different ways. I saw it first with Harry King while playing recreational sports, then later at the horse track.

Recreational sports is loosely defined in this case as a 16-year-old copy boy at the Arkansas Gazette, who was included in touch football games during dinner break in the street in downtown Little Rock. No one competed harder than King.

Those games stopped after repeated ankle sprains from the curbs, or manhole covers. My father, the sports editor, got tired of seeing King on crutches.

There were also home run derby games at the Little League field at Junior Deputy. The games were fierce.

Then, there was the 4-ball tournament at old Riverdale Golf Club. Paired with King, we drew two of my UCA college teammates in the first round. Six holes deep we found ourselves three down, despite making four birdies.

“Get your butt in gear,” King whispered into my ear. “We aren’t going to lose. Make more birdies.”

More from WholeHogSports

https://www.wholeho…">Harry King's farewell column

We did. We got the match into extra holes before losing on a chip-in. We were 7 under on our 20 holes. I felt good about the effort. All King said, “We didn’t make enough birdies. I don’t like to lose.”

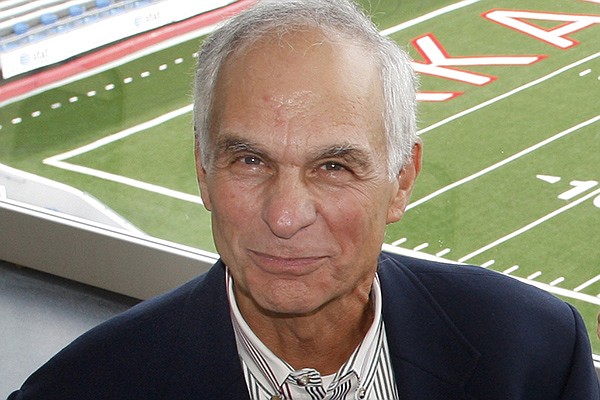

That was not just in golf or other recreational sports. King, writing the last time for Hawgs Illustrated in this issue, showed winning form with his work. He competed fiercely through the years. He won during a long career with The Associated Press, then at Stephens Media.

He rose to the rank of news editor at AP in Little Rock while also being designated as an AP sportswriter, a title reserved for only the best. He eventually had to choose one or the other and retained his sportswriter title, even though he had to give up some benefits to do it. He covered high school and Razorback sports while also taking on news assignments. I don’t know anyone who could do so much so well.

That’s why Dennis Byrd, chief of the Arkansas News Bureau for Stephens, hired King away from AP to cover the Razorbacks and write columns for their papers statewide.

“I worked for Harry at AP, then I was his boss at Stephens,” Byrd said. “It was never about one or the other being in charge; it was about working well together and growing a friendship. I knew he had more sports knowledge in his head than anyone and his work ethic was second to none.

“I always said that Harry had an impact on many people in Arkansas who never heard of him. For example, he wrote the high school sports roundups that ran in virtually every paper in the state, often only under the byline ‘By The Associated Press.’ He picked the player of the week and compiled their highlights. He also covered the Razorbacks and was the best in the state.

“We all knew that he loved what he was doing and could go anywhere in the country with AP. He could have gone to New York or several other places, but love of family and his hometown were more important than his career.”

That’s exactly what Warren Stephens said, the reason he gave Byrd the thumbs up to hire King when his company bought Donrey Media. King was the replacement when Orville Henry died.

“Harry King is one of the giants of Arkansas sports journalism,” Stephens said. “Very few people come to mind to fall into his category. I’m talking about ability and longevity. Frankly, I can only think of Orville Henry, Bud Campbell and Wally Hall.

“Harry knew the passion our state felt for the Razorbacks. As a reader, I wanted true insight and that’s what he gave me. Over and over, I’d pick up Hawgs Illustrated and read the first two columns in the magazine and that’s where I found insight. It was the kind of thing I couldn’t wait to tell my co-workers and friends.”

Stephens said some of his most treasured memories were flying to and from the Masters with King in his private plane.

“That’s where I got to know Harry,” Stephens said. “One of my favorite memories was at Augusta National while watching the Masters. I climbed into what we called the observation tower (reserved for members and media) and over in the corner was Harry with his notepad and pen. His golf coverage was outstanding, always insightful.

“I was there at the Masters and what Harry wrote was something I hadn’t known. I’m talking about an elite writer. It was concise and brilliant.”

That carried over to Razorback coverage. It’s why my first call after starting Hawgs Illustrated was to King. Would he write a column? I got a comical response.

“I don’t know if I write columns,” King said. “I’m not sure if anyone would want to read my ramblings.”

I knew how important it was to get his work in the magazine. I drove to North Little Rock to sit in his living room. I urged his wife, Ellen, to push for a commitment. I stayed in their home overnight to make sure it was going to happen.

Generally, there was no need to assign story ideas. He almost always came up with unique takes.

The cool thing on Sunday morning was to get his summary of the game. Almost always King did in 800 words what I failed to do in 2,000.

A really fun thing was to send King a feature to edit. Could he make suggestions? Would he clean it up? It would come back about 200 words lighter and you couldn’t figure out what was gone.

Never did anyone type faster in the pressbox. King confessed that he was probably at 90 words a minute at one point, but can’t hit that rate now.

“For a while, John Brummett was the fastest typist at the Arkansas News Bureau,” Byrd said. “I told Brummett he’d soon be second fastest. He looked up questioningly, and that’s when I told him Harry King was joining us.”

While King was a fast typist, it always was quality over quantity. It was getting it right as well as getting it out quickly. Your reputation as the state’s top sports writer is earned by getting it right every time, not just breaking a few stories. King did both, often.

What I recall more recently is that he always finished first in the pressbox at Razorback games. He’d write and re-write leads throughout the game. He was ready in the closing seconds to deliver a solid column with the most important details. He could hit send before anyone else went to the locker room.

When I returned to my seat, King would usually be reading copy. When I finished, he’d slide into my seat. He always helped my stories. He could point to a paragraph in the middle of a column with this: That’s your lead.

There was one other key duty King provided for Stephens. We’d have nine sportswriters and photographers on the Falcon jet provided by the company. King was always our van driver when we hit the ground.

“There are stories about Harry driving the van a little fast between the airport and the stadium when our timeline was a little tight,” Byrd said. “We only got a 13-hour window from wheels up in Little Rock, grab a crew in Fayetteville, make it to Gainesville or Tuscaloosa and back home. Harry tried to make up some time on the ground.”

I was navigator. I’d made more of those road trips than anyone in the vehicle. There was a trip before turn-by-turn navigation on smart phones when he misinterpreted my directions. He went the wrong way on a one-way street leaving the airport at Auburn.

“It was quicker,” King said to the protests as we piled out at media parking. “You guys just make deadline after the game. I got you here just fine. And maybe I’ll go the right way on the one-way street going back. Maybe not.”

One of those in the traveling crew was Matt Jones, now a regular at Hawgs Illustrated. He said he grew up reading Harry’s columns while delivering the local paper in Fort Smith. “He’s the reason I went into journalism,” Jones said. “He almost always wrote about the Razorbacks, and he inspired me to want to do the same.”

None of those plane trips beats my favorite on-the-road experience with King. We took my two-seat Ranger pickup to the 1994 Final Four in Charlotte. Our luggage had to be wrapped in garbage bag because of spring rains.

Family concerns — and family was always top priority with King — led us to plan a quick getaway from Charlotte after the net cutting. Ellen had been battling an illness.

“Do you want to drive back right after the game?” King asked when I got to the arena. “I think it’s about 12 hours to North Little Rock.”

I thought that sounded crazy, but doable. That would be after I returned to my hotel, packed and checked out. We agreed to do it, knowing we could split the time at the wheel.

When the Razorbacks won, it delayed departure a little because it was a long wait until President Bill Clinton got out of the locker room. There was no Internet in those days, so my magazine deadline wasn’t for another week. I hustled back to the hotel, then picked up King at 2 a.m. Off we went.

The early part of the drive was easy. There was talk of the game, the post-game celebration and even what I saw at the team hotel (my hotel) as the team returned to hysteria.

Then, somewhere in east Tennessee as the sun came up, the adrenaline left. That drive across Tennessee was the longest of my life. Two-hour driving shifts turned into just one hour. Somewhere around Forrest City we started swapping seats every 20 minutes.

We debated whether the passenger-side man should sleep or tell stories to keep the driver awake. Somewhere around Carlisle there was uncontrollable laughter from King.

“I’m about home, but you have three more hours to get to Fayetteville,” he said.

That’s typical King humor. It’s always dry and beautifully done.

But, it’s always followed by a warm solution. He suggested that I either take a nap at his home, or spend the night.

I’m just like him, getting home was the goal. It always has been with King.

There’s never been a more loving husband or father. I’ve seen that side of him so many times.

King made me feel like family. One of my favorite memories came just out of college. He asked me to come watch his son, Petey, hit a few golf balls. He thought he might make a good golfer, but didn’t want to steer him wrong.

Petey, 12, was playing in a baseball tournament at Burns Park. I drove from Conway to meet them behind the outfield fence to watch a few golf swings. The only thing I did was check his grip and suggest a bigger shoulder turn. The rest should fall in place in good time.

Already tall for his age, Petey had a natural swing and could smash it with his long limbs. He would become one of our state’s all-time greats. Competing on the same stage as John Daly, they each won five state amateur titles before and after their time as Razorback teammates.

I loved hearing stories of Harry caddying for his son in those state tournaments, some insights to a victory. I also recall their reactions about botched shots or intense pressure applied by the other in state father-son events.

“We’ve had a lot of fun together in golf,” said Petey, now one of the state’s top golf instructors. “But one thing that always frustrated me was that he’s never given up the goods when he’s covered the coaching searches.

“There were times that I knew he knew exactly what was about to happen. I’d ask and he’d say, ‘Son, you know I’m not going to tell you.’ And, he never would. If he had to keep a secret until the story ran, he did.”

Another favorite memory was with Harry and Petey at the racetrack while covering the second Arkansas-Oklahoma matchup in the Orange Bowl. There was an off day from practice on Jan. 31. The three of us went to Gulfstream Park.

My idea of gambling at the races is simple: put $40 in one pocket that covers the admission cost, lunch, the racing program and a few bets. I never go into my wallet.

At the end of the day, I asked Harry for advice for my last wager. I failed to mention that I only had $2 left in my pocket.

“Bet the exacta on the two long shots,” he said. “It looks like it’s 10 and 11. That’s even better because most don’t do double-digit exacta bets.”

That was in the days when you had to spend $4 to bet a two-horse exacta with each horse on top. I just picked one and bet the other second. At the finish, I had both horses, but not in the right order. As the horses crossed the finish line, Harry and Petey started dancing. The winning price was $2,800.

“Dinner is on Clay,” Petey said.

“We are going to Don Shula’s Steakhouse,” Harry added.

I just tossed my losing ticket to the ground. Harry ran to scoop it up and immediately was dumbfounded.

“You didn’t bet it both ways?” Harry said. “I would have given you another $2. Tell me you’ve got another ticket. Please.”

There was silence on the ride back to the hotel. I wasn’t upset, but it was clear that Harry was furious. I tried to explain to our wives later at dinner.

Dead serious, he finally said, “There is no excuse for losing.”

That’s the ultimate competitor. I’ve known him all my life. If you are going to pick a co-worker or a 4-ball partner, pick a winner, Harry King.