FAYETTEVILLE — When there is talk about the Arkansas team that won the 1964 national championship, there will invariably be some that downplay its physical talent. Mainly that comes from the players themselves.

They point to football smarts and coaching as the clear edge that helped them roll to an 11-0 record. They acknowledge that Texas, the defending national champion, was loaded with superior talent.

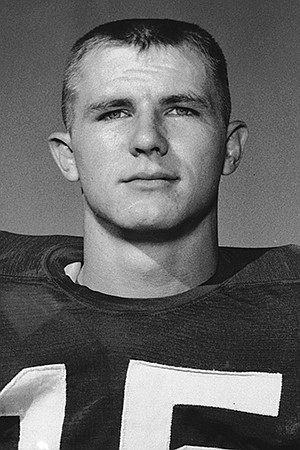

But, to a man, they always point out that there were some top athletes sprinkled throughout that Arkansas team, starting with Harry Jones, the Enid, Okla., product with size and blazing speed.

Jones started as a true sophomore at safety, perhaps the most fun position to play on a team that shut-out the last five opponents on the way to the Southwest Conference championship and the Cotton Bowl. Jones always downplayed his role with that defense, pointing to a front that featured great linemen and linebackers, and coaches that maximized their talent with amazing stunts and technique.

“I've always said that I had the best seat in the house to watch the greatest defense to ever play the game of football,” Jones said in 2014, just days before the 50-year reunion of the national championship team.

“In those days, there were very few long passes attempted. Tulsa did throw some, Baylor, too. But that was about it.

“Then we got on that run of shutouts, but I never really felt pressure that if I didn't make a play the streak was over. It just wasn't like that with our front eight. They made all of the plays.

“There wasn't much publicity on what we were doing, either. There was no ESPN to talk about our string of shutouts.

“Now we knew we were pitching shutouts, but it wasn't talked about outside of our locker room. We took pride in it. I took some kidding, too, that I wasn't having to do too much back there at safety.”

A lot of it came from linebacker Ronnie Mac Smith.

“Ronnie Mac kept saying, 'Do you ever have to make a tackle?'" Jones said. "I was a sophomore and I just put up with it."

There were some tackles, but there weren't a lot of plays left after linebackers Ronnie Caveness and Smith were finished. Jones did make 49 tackles. He also had five pass breakups and two interceptions, both returned for scores.

There was one tackle that all recall, one that was wiped out by a Texas penalty. However, it's still worthy of discussion at reunions. Ernie Koy, the great Texas running back, found daylight in the '64 game at Austin and Jones had to get him down.

“It came down to just me and him,” Jones said. “It was probably the first time it came down to just me on a running play. I went for his legs and wrapped up. I held on and he drug me about 10 yards.”

It produced some chuckles in the film review the following day, especially after secondary coach Johnny Majors finished.

“Coach Majors was laughing,” Jones said. “He kept running it over and over. He said, 'I guess you could say you got him down, but you looked like you'd been in a fight after that play.' He was about right.”

There were none that could outrun Jones. He was never timed in the 40-yard dash, but there was lightning in his 6-2, 195-pound frame. He clocked many 9.6s in the 100-yard dash in college.

Eventually, Jones was dubbed as "Light Horse Harry," but there were no nicknames in '64. That came after the public address announcer blurted it out during the 1965 TCU game, after he stunned Oklahoma State with a series of big plays at wingback as a sub for injured Jim Lindsey.

“I had never had a nickname,” Jones said.

Soon there was a song on the radio with part of the lyrics: Run Harry run, run you son of a gun, give that ball to Harry Jones.

“Someone came into the dorm singing it,” Jones said. “I didn't believe it. But later I was in the student union and they were playing it there. I got a lot of kidding about that.”

Then there was Jones on the cover of Sports Illustrated after the 27-24 victory over No. 1 Texas in 1965 - the first time for a Razorback to be so displayed.

Jones autographed copies of the magazine for the next five decades. They came in the mail, from all over the country.

“It was about five years ago, they had a legend tent at the spring game,” Jones said. “I signed autographs. It was so hot that day. I didn't think there would be too many come to the tent. When I got there, the line was as far as I could see and a lot of people had that old SI magazine. I stayed until they were all signed.

“Those magazines were 45 years old and people still had them. I couldn't believe it. People told me they had been waiting all of these years to meet me and get them signed, or handed down generation after generation.”

It reminds him of the special nature of Arkansas fans.

“I knew it right away when I was recruited from Enid,” Jones said. “My parents came to all of the games and they had a great time wearing the No. 23 badge for my number. It was really an incredible three years.”

Then there came five years in the NFL with the Philadelphia Eagles. His vertical running style made him an easy target for the great linebackers. Dick Butkus destroyed his knee. There was no wingback position in the NFL, only tailbacks or halfbacks.

“I wasn't either,” said Jones, a quarterback in high school. “I would have been better off in the NFL at free safety, my best position. I could have played forever. I ran straight up. You take too much punishment.

“Coach (Frank) Broyles used to yell at me all the time. He'd say, 'Body lean, body lean.' I never did learn.”

It was just safety in '64. He thought he was going to be the quarterback as a junior, but Jon Brittenum won the battle in the fall.

Jones, the son of an Enid minister, was advertised as the next Billy Moore - a great running quarterback - when he picked Arkansas over Oklahoma. He spurned OU's recruiting partly because he felt unappreciated by Bud Wilkinson, the famed OU coach. He loved Arkansas defensive coach Jim Mackenzie, who would later become the Sooners' head man.

“Wilkinson never visited my home and he wasn't on campus the day I visited OU,” Jones said.

With Freddy Marshall and Billy Gray settled in at quarterback, Jones was tried at safety in the spring 1963.

“I was just lucky I got to play in '64 because I was terrible in that spring,” Jones said. “I thought I was for sure going to be a redshirt.”

But after a summer working the Enid hay fields, Jones arrived in the fall of '64 with more strength and speed.

“I don't think I ever was better than 10-flat in high school,” he said. “But I was the fastest guy on the team when we came back in August. I was much stronger.”

Late in the week before the opener, Majors pulled Jones aside as they walked to the field house after practice.

“Coach Majors said they were thinking about starting me,” Jones said. “He said, 'Do you think you can handle it?'”

Majors sensed some panic with Jones. Indeed, there was. With news that he would play, he knew his dad would make the drive from Oklahoma.

“I had to find him tickets because I had sold mine,” Jones said. “I don't think he missed another game.”

Jones didn't think that would be the start of a run to the national title.

“No one knew what we were going to be,” he said. “We weren't picked in the SWC. We were coming off a poor season and were not even ranked.

“But we got things right in the spring. Usually, seniors didn't scrimmage in the spring. Those seniors – and there were some great ones – put themselves in the scrimmages. It was horrific as far as the amount of contact and those that survived led us to the championship the next fall.

“You know them, all of the big names in Arkansas football history. I still count myself very lucky to get to play with them. Not many sophomores did in those days.

“I remember someone saying during the early part of the '64 season when Loyd Phillips and I both started, that it was not a good sign that sophomores were starting.

“The common phrase then, you'd lose two games for every sophomore you started. It didn't hurt that both of us would be first rounders (in the draft).”

Jones went from the NFL to coaching, joining Majors at Pitt where he was eventually assigned to the backfield. He tutored Tony Dorsett as the Panthers won the national title in 1976. Dorsett won the Heisman Trophy and gave his helmet to Jones.

“My goal was to coach, go up the ladder, eventually return to Arkansas as head coach some day,” Jones said. “But I got frustrated in coaching. I couldn't dedicate my life to that. You never see your family. I couldn't do it.”

Jones realized, too, that there was something special about Arkansas that didn't exist anywhere else.

“In pro football, I saw the way players felt about their school,” he said. “They didn't have the same feelings that Arkansas players had. It's never gone away for me.”

Good vibes have always been there for Arkansas fans toward Jones, too. He was an instant star in '65 when he was converted to wingback as Lindsey's backup after losing the quarterback battle to Brittenum.

Actually, Jones thought all through the summer that he was going to play quarterback. It had been too close to call in the spring, but there was a call from Broyles in the summer which signaled a decision had been made.

"Coach Broyles called me and told me not to tell anyone, but I was going to be his quarterback," Jones said. "I didn't even tell my parents. But when we got to school, I saw the depth chart. It had me, Ronny South and Jon Brittenum all listed as first team.

"I don't know if it was an attempt to keep from hurting any feelings or what, but I didn't think too much about it. But in two-a-days, Jon clearly outplayed me."

Then on the Monday before the opener against Oklahoma State, Broyles broke the news: Brittenum would be the starter. He also had a proposition: Would Jones play tailback, wingbnack or wide receiver?

"It broke my heart," Jones said. "But I said I'd do it. Whatever was best for the team.

"But I went to Little Rock for the opener confused and in a state of shock. I'd really never played anywhere but quarterback on offense my whole life. But the next four or five weeks changed my life. It was storybook stuff, like Cinderella."

It was 0-0 late in the fourth quarter when Jones got his first taste of wingback.

"They sent me in with a play, but Jon checked out of it to a pass for me," he said. "He threw it to me and we made a first down.

"I looked to the sideline, thinking I was coming out. But they left me in. They called another play, Jon checked off to the same pass to the other side, another first down."

The next play, another audible to Jones, went for a touchdown.

"I sat out after that," he said. "Then, late in the second quarter, we ran an option play, Jon pitched to me and I went 50 for a touchdown. I had never run with the ball in my life. Holy cow! I ended up with 120 yards, six runs and five catches.

"After that it just kept getting crazier and crazier. Jim Lindsey got hurt and I got to play against TCU. I carried the ball and the stadium announcer said, 'That was Light Horse Harry Jones.' And it stuck."

A previous version of this story was published in Hawgs Illustrated