FAYETTEVILLE — There is little doubt that Barry Switzer was one of the all-time greats in coaching. He led Oklahoma to three national titles, 12 Big Eight crowns and then coached the Dallas Cowboys to a Super Bowl win.

But when the Hall of Fame coach pairs “we” and “national championship” in the same sentence, Switzer also might be talking about his first crown, as an assistant coach for Frank Broyles when Arkansas won the 1964 national title.

I covered Switzer as a beat writer for the Tulsa World from 1978 until Switzer resigned in the late spring of 1988. Many times, he'd ask about Broyles because I was also covering some UA games. He always beamed of his ties with the Razorbacks in those conversations. He might quickly switch into “we” when talking about the goings on in the Ozarks.

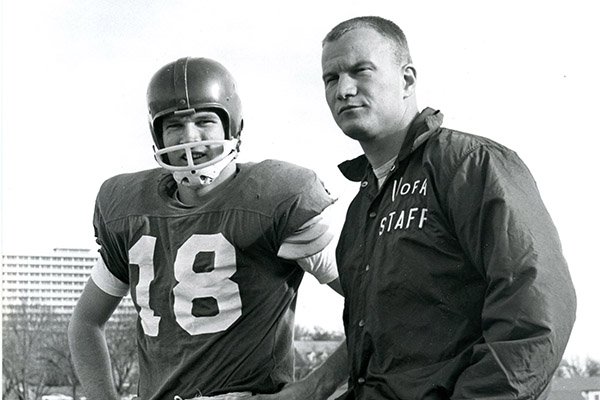

Switzer is just as proud of serving as one of “Frank's first captains” when the 1959 Razorbacks broke through in Broyles' second season for a share of the SWC title. And, he's just as proud that Broyles asked him to coach for him and got him out of the U.S. Army to join his staff.

“I was recruited by Bowden Wyatt, then played three seasons for Jack Mitchell,” Switzer said. “I'm so glad it worked out that way. The highlight was being on Frank's first two teams. That's why I got into coaching, because of Frank. I will forever be grateful to him. I never intended to be a coach.”

Switzer laughs about stories from Bob Stoops about following his father into coaching. Switzer said he tried not to follow anything his dad did.

“My dad was a bootlegger,” Switzer said. “If I followed his steps, I would have been in prison. But coaching was never in my thoughts.”

Switzer maintains his plans in college, especially at the end, were to enroll in law school after mandatory military service.

Switzer did get some coaching experience while finishing up his degree requirements in 1960. It included working with the freshman team.

“I was assigned to help (defensive coordinator) Jim Mackenzie with recruiting,” said Switzer, always a magician with that part of coaching. “A player would get to campus and they would give them to me for the tour. I gave the young recruits attention and our coaches noticed. Coach Broyles saw it.”

Then came military service, as required in those days.

“You do six months; everyone did,” Switzer said. “I picked the Army. They sent me to Aberdeen Barracks in Maryland.”

It was the summer of 1962 with Switzer lacking four months to complete his six months in the Army.

“I got a call over the loud speaker to report to the commander's headquarters to take a call,” he said. “It was Dixie White, my offensive line coach under Mitchell and Broyles. He said, 'Barry, Coach Broyles would like you to come back and coach and run the scout team.' He wanted me back Sept. 1 for two-a-days. I told him I was in until the middle of October and it wouldn't work.”

Switzer thought that was the end of the story. He told White that there were plans for law school anyway.

White was ready to help expedite his return to Fayetteville. He was given the name and address of someone in Washington, D.C., with Arkansas ties with the possibility of an early exit from the Army.

“I was told to go to the commander and tell them I was planning to get out early and fill out a form,” Switzer said. “When I asked him for the form, all he did was laugh in my face. He said there had been hundreds and hundreds of that type form filled out. They filled his file cabinet. None were granted.”

Five days later Switzer heard his name called on the loud speaker at the parade grounds again. Private Switzer was to report to headquarters.

“The commanding office asked me in and he pushed a manilla envelope across his desk,” Switzer said. “I looked at the return address. It said Wilbur Mills, Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.”

That was three years into the 17-year stint Mills served at the head of the Ways and Means Committee, perhaps the most powerful seat in Congress. He controlled the funding for the military and about everything else in national government.

“I guess Frank had pretty good friends,” Switzer said. “The commanding officer said, 'Private, this is the first one of these I've seen. You know someone pretty powerful.'"

Indeed.

Broyles became one of the most powerful men in Arkansas pretty quickly. Switzer was there for the early years of a great ride.

“I sure was,” Switzer said. “I didn't mean to get into coaching. I told Dixie White that. He just responded, 'Coach Broyles has a pretty good job for you. It's a free place to live, the dorm. Everything is paid for. You will work with our offensive line.' I got to thinking, this isn't bad. Law school can wait. Plus, I was getting out of the Army.”

Even when he got to Fayetteville, there was a visit with Broyles that emphasized that law school was the ultimate goal.

“I went to see him and found out what he wanted me to do in the dorm,” Switzer said. “I was to be the discipline guy. I really didn't think that was great. I was going from being good friends with players to the guy who had to get after them when they missed up.

“So I told Coach Broyles I'd do it, but I wasn't going to do it for long. He said, 'Barry, just give it one year and then you can go to law school.' I agreed and then I never left coaching. I'm thankful that he was persistent in getting me back from the Army. I would have never been in coaching except for what he did that summer.”

Switzer was elevated to full-time assistant in '64, working with Merv Johnson to coach the offensive line for two seasons. When Mackenzie became head coach at Oklahoma in 1966, Switzer followed him. Mackenzie died of a heart attack after his first season. Switzer would later become head coach at OU after Chuck Fairbanks went to the NFL in 1973.

Switzer won national titles at Oklahoma in 1974-75 and 1985. Johnson was his O-line coach in '85. Switzer was the first call Broyles made when he decided to retire as Arkansas coach in 1976. Switzer said no and that led to the call to Lou Holtz, Broyles' successor.

Switzer's son Greg played outside linebacker for the Razorbacks, lettering in 1988-91. Out of coaching, Switzer found himself in the UA press box for many games and served briefly – asked by Broyles – as the color analyst for the radio broadcast.

It shouldn't surprise anyone that Switzer would quickly slip into “we” talk when the Razorbacks were rolling. And, there would always look for Broyles for a handshake that he pulled into a bear hug.

After all, if it was not for Broyles, Switzer would have turned out to be a lawyer instead of a Hall of Fame coach.